The social network’s defense of President Trump has cost them.

Although Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has acknowledged his company’s role in geopolitics—from Russia’s misinformation campaign prior to the 2016 U.S. presidential election to serving as a platform for inciting ethnic cleansing in Myanmar in 2018—it is the company’s recent defense of President Trump that is prompting businesses to halt ad buys.

The Wall Street Journal reported on Saturday that Disney has joined an international list of more than 1,200 small businesses and multinationals to engage in an advertising boycott against Facebook as part of the Stop Hate for Profit campaign. The initiative is led by organizations including the NAACP, Free Press, Sleeping Giant, and the Anti-Defamation League.

“The goal of #StopHateForProfit is to compel Facebook to get serious about curtailing the spread of racism and bigotry across its network,” says Free Press Senior Director of Strategy and Communications Timothy Karr, noting the coalition has issued 10 recommended next steps. “The company has a long history of promising to do more, followed by little to no action or enforcement.”

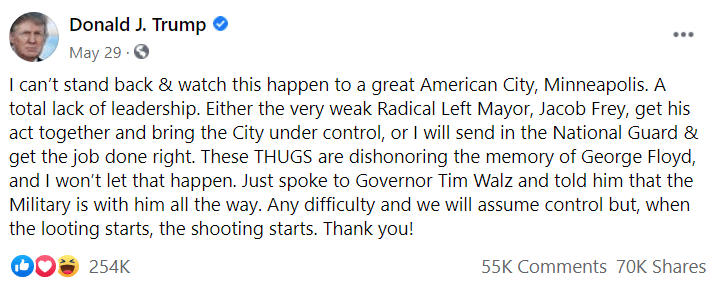

Trump’s comments following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis is at the core of the corporate advertising boycott. While Twitter hid the content for “glorifying violence,” Trump’s words remained intact on Facebook:

Although Trump claims ignorance of the origins of the “looting…shooting” phrase, according to NPR, its origins date back to 1967 when a Miami police chief uttered the words and said he didn’t mind being accused of “police brutality.”

Free Speech

To be clear, hate speech, even inciteful speech, is a fundamental American right. Facebook has done nothing illegal by keeping the president’s comments online. The First Amendment prohibits government censorship of speech unless it presents a “clear and present” danger. What we’re seeing is a backlash against the president among a large swath of the citizenry and the private sector.

Facebook and other social media platforms have “a fine line to walk,” says Summer Lopez, Senior Director of Free Expression Programs at the literary human rights organization PEN, which has not taken a stance on the advertising boycott.

“As a free expression organization, we are wary of granting [Facebook] too much power to moderate public speech,” she says. “But as we have examined in our two reports on the subject [Faking News and Truth on the Ballot], and as we have seen in our ongoing work to support writers and journalists in defending against online abuse, the deleterious effects of hateful speech and disinformation can also ultimately distort and silence meaningful online discourse.”

The Facebook advertising boycott represents an international reckoning. Advertising on a platform where racism, hate speech, and misinformation run unchecked is bad for business. One could argue that the boycott was inevitable. Marketers are now judging Facebook unsafe just as some did when cutting financial ties with Breitbart News several years ago.

The Impact of Boycotts

In 2016, Kellogg boycotted the alt-right, pro-Trump news outlet—run at the time by former Trump advisor Steve Bannon—after it published a series of inflammatory articles including a misogynistic piece on birth control and female attractiveness.

Kellogg has not joined the Stop Hate for Profit Facebook boycott, whose supporters include Starbucks and Unilever, the London-based holding company with brands including Vaseline, Ben & Jerry’s and Lipton.

What, then, should marketers do with the dollars they are withholding from Facebook? The non-profit organization representing the North American news industry says it’s time to reinvest in professional journalism.

“Facebook is one of the two major ways Americans get their news,” says David Chavern, CEO of News Media Alliance. “One of the things I’ve always said to Facebook: If you have a fake news problem, a misinformation problem, we’re in the real news business. We should be an answer to a lot of their problems.”

Dear Facebook

The Arlington, Va.-based organization is running a “Dear Facebook Advertisers” ad campaign urging advertisers to increase their ad spend with professional news organizations. In line with the advertising boycott, NMA is not advertising on Facebook although it has made an ad buy on Twitter, says Communications Director Lindsey Loving.

“There is a concern among advertisers…[that] they are supporting a platform that amplifies hate and dissension,” Chavern says. “We are making the point to advertisers: We create quality. We are professional reporters and professional editors. The topics we cover are not always easy, but we are serious. We are a good, safe place to place your advertisement.”

Newspapers could use the cash. Many have been giving their Covid coverage away for free to provide fact-based media coverage as a public service. But larger trends are at play. As Facebook and Google ad revenues have skyrocketed over the years, ad revenues at news organizations have declined.

In 2006, when Facebook had a mere 12 million active users, ad revenue for U.S. publicly traded news publishers totaled $60 billion, according to NMA, which changed its name from the Newspaper Association of America in 2016.

Facebook began selling ads in 2009, bringing in $777 million that year. Last year, its ad revenues totaled nearly $71 billion. The news industry pulled in $14.3 billion in ad revenue in 2018.

Facebook and Hate Speech

Something else has mushroomed, too—the number of times Facebook is associated with hate speech. One might think brands would be flocking to professional news outlets given this dynamic, or joining the advertising boycott, but that is not necessarily the case.

A recent Google search for “hate speech misinformation Facebook” yielded 8.97 million results. Despite Facebook’s dwindling reputation as a stand-up business partner, some brands are refusing to advertise on news sites next to stories on the pandemic or protests—issues that the public clearly wants to learn about.

“There has been a trend of advertisers shying away from news because news can be controversial,” Chavern says. “The Wall Street Journal has reported that Target is holding back advertising from things related to protests” and that other brands are doing so with Covid-19. “What they’re doing is intentionally not supporting the journalism we all need now.”

But research shows that Target is missing the mark.

In fact, “bad adjacencies”—the idea that running an ad next to hard news or serious topics is bad for a brand—is a myth, says NMA.

Rebecca Frank, VP of Research and Insights, cites two reports demonstrating that advertising next to hard news is good business. The Hard News Project: Why Avoiding Hard News Could Be Bad for Your Brand, published by London-based Newsworks, argues that the “average ad dwell time is 1.4 times higher in a hard news environment (45 seconds versus 32 seconds)” than in a soft news environment.

“While the average levels of response to ads in hard and soft news environments are similar, the pattern of response shows more and stronger peaks for ads in a hard news environment,” the report states.

“This indicates that the brain is more actively engaged and there is more likelihood of key messages being encoded into memory.”

In Content We Trust

NMA’s Frank also points to the April 2020 report by ad industry trade group the 4A’s, Cross-Industry Collaboration to Redefine Brand Suitability in Trusted News Environments: A Call to Action. Ninety percent of people respond favorably or neutrally when ad adjacencies appear next to serious content like Covid-19.”

Indeed, the 4A’s Advertiser Protection Bureau has united advertising holding companies, the Interactive Advertising Bureau, and other groups around the concept that “journalism is critical to democracy.”

“One major finding of this project is that trusted news content is brand-safe,” write the authors. “This finding should reassure the industry that investing in trusted news media does not support individuals or organizations that espouse or promulgate hate speech and/or promote disrespectful and harmful treatment of sensitive social topics, such as abortion or extreme political positions.”

Free Press, one of the Stop Hate for Profit organizers, is likewise aiming to turn its anti-Facebook advertising boycott into new revenue streams for local journalism “at a time when tens of thousands of reporters have lost their jobs,” says Timothy Karr, co-author of the report, Beyond Fixing Facebook.

“One of our recommendations calls for a tax on targeted ad revenues, the meat and potatoes of social networks like Facebook,” Karr says. “We’re in ongoing conversations with several members of Congress. These include this idea alongside other efforts to revitalize local, independent journalism.”

The proposal would place a 2% levy on online advertising, up to $2 billion a year for a media endowment.

Given the IAB’s opposition to other advertising taxes, garnering widespread industry support for such an initiative would be difficult.

Election Misinformation

Brands and publishers need to focus on the here and now, Chavern says. The 2020 presidential election is 106 days away.

“You’ve got crazy misinformation and dangerous lies and deep fakes, and other things that can really impact an election; a lot of that flows through Facebook. If you’re an advertiser concerned about hate speech, you should care about misinformation because that’s going to get dark.”

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

N/A on

So news publishers are promising powerful corporate marketing interests a “good, safe place,” where never is heard a discouraging word, nor any hint of bothersome “dissension”?

What strange times.